Nine weeks after a gunman tried to kill Donald Trump in Pennsylvania, the FBI said the former president appeared to be the target of another assassination attempt, at a Palm Beach golf course on Sunday.

He was not injured. But these successive incidents have historical echoes. In September 1975, President Gerald Ford escaped two assassination attempts, one in Sacramento, the other in San Francisco.

As with the political violence this summer, the assassination attempts on Ford shocked the nation.

Here’s a look back at what happened, from the pages of the Los Angeles Times.

September 5, 1975 | Sacramento

Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme, a Charles Manson follower, was 26 when she pulled a gun on Ford in Sacramento. Secret Service agents caught her and Ford escaped unharmed.

She was convicted on November 26, 1975, of attempting to assassinate the president. She was released from prison in 2009 after 34 years.

In a 1975 testimony, published decades later, Ford calmly described seeing a woman in a bright red dress in Capitol Park in Sacramento and thinking she was approaching to shake his hand.

“My first impression was that she wanted to come over and extend – I thought at the time – a hand to shake or to say something to me,” Ford says on the tape.

He then said he noticed the weapon, a Colt .45-caliber semi-automatic pistol, adding that “the weapon was large.”

The Times’ Christopher Goffard covered the story earlier this year.

He spoke to witnesses in Sacramento and also looked into Fromme’s obsession with Manson.

Journalist Jess Bravin, author of “Squeaky: The Life and Times of Lynette Alice Fromme,” told Goffard that Fromme maintained a kind of religious devotion to Manson until his death. She told Bravin that she went to the park that day, not knowing what she would do.

“She had no personal feelings about it. [Ford] “In some way,” Bravin said. “She was very angry at the system and what she felt was environmental degradation. Ford would come and talk to businessmen in Sacramento. She felt like he was destroying the redwoods.”

In 1987, after hearing a rumor that Manson was dying of cancer, she escaped from a minimum-security federal prison in West Virginia in hopes, she said, of being near him. She was captured two miles away.

She was released on parole in 2009.

President Ford is brought to safety after Lynette Fromme attempts to shoot him on September 5, 1957, in Sacramento.

(Associated Press)

September 22, 1975 | San Francisco

Sara Jane Moore, an accountant and divorced mother of four, was fired from Ford’s job on September 22, 1975, as the president was leaving a conference at the St. Francis Hotel in downtown San Francisco.

His single shot from a .38-caliber revolver missed Ford by several yards after Oliver Sipple, a disabled Vietnam War veteran, grabbed her arm and pulled her down.

San Francisco police had dealt with Moore in the past and considered her a potential threat to the president.

Two days before the assassination attempt, they had stopped her on the street with a .44-caliber revolver in her handbag and boxes of ammunition in her car.

The police alerted the Secret Service, who questioned her and released her. Less than 48 hours later, she bought her .38 from a friend, stood in front of St. Francis Church in a crowd of several thousand, and tried to make her way into history.

Before shooting Ford, Moore had received several psychiatric treatments. Her lawyers were preparing an insanity defense. She pleaded guilty despite their objections.

After being convicted, Moore expressed mixed feelings about her actions.

“Am I sorry I tried?” she said. “Yes and no. Yes, because it didn’t do any good except ruin the rest of my life. … And no, I don’t regret trying, because at the time it seemed like an appropriate expression of my anger.”

Sipple, the former Marine who subdued her, said his life was ruined by the publicity he received following his heroic act.

A retired Marine on disability pension, Sipple was gay – a fact he said his loved ones never knew until it was revealed in the newspapers.

He filed a $15 million lawsuit against seven newspapers, including the Times, for invasion of privacy. A judge dismissed his claim. Sipple died in 1989 at age 47. His health had deteriorated and he was drinking heavily.

That year, Ford wrote a letter saying he was “eternally grateful” for the former Marine’s actions in preventing the assassination.

“I deeply regret the trouble he has encountered as a result of this incident,” Ford wrote in his letter, dated Feb. 14 and addressed to “the friends of Oliver Sipple.” “I was saddened to learn of the circumstances of his death.”

Moore was released on parole in 2008.

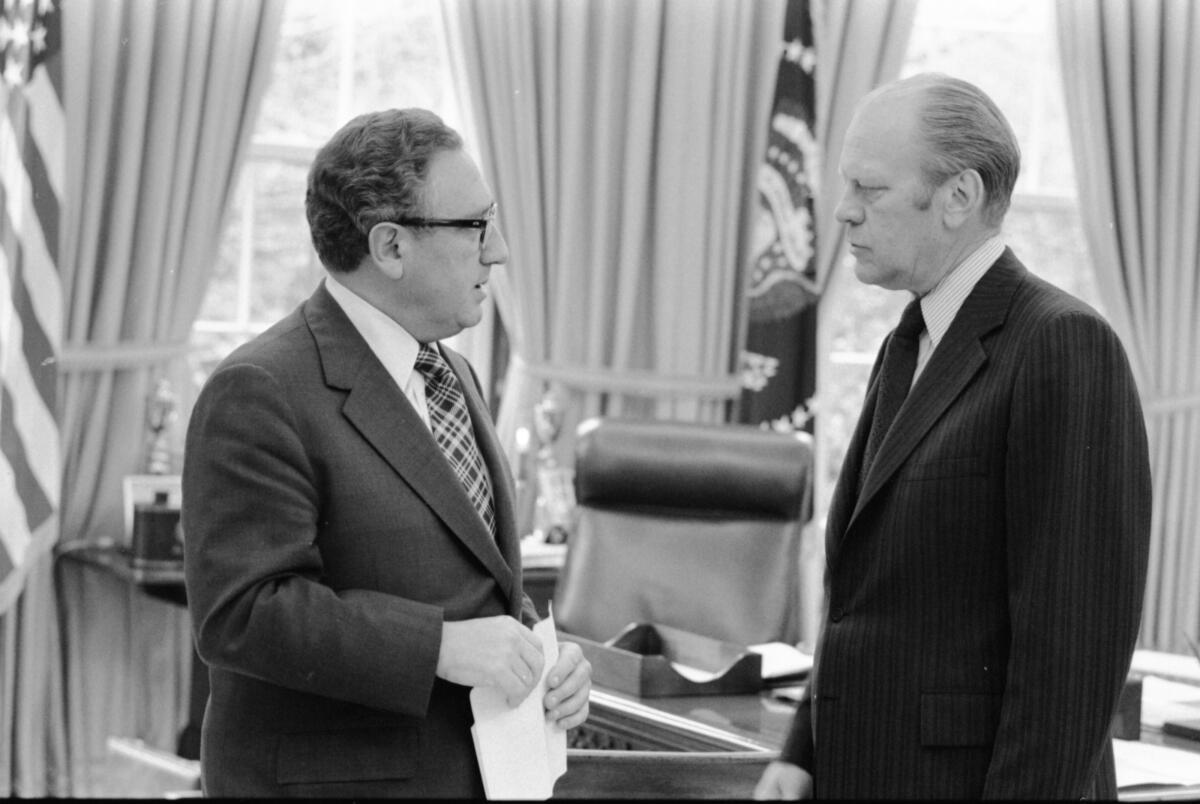

Gerald R. Ford and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger in the Oval Office.

(David Hume Kennerly / Gerald R.)

Evaluate these moments in history

In 2006, The Times looked at both assassination attempts and found that they had become footnotes in history. Historians have analyzed their significance.

Both plots are symptoms of the 1970s, the “wackiest decade of the century for California … in terms of its uncanny strangeness,” said Kevin Starr, a USC history professor and state librarian emeritus.

“Moore’s style was middle-class, while Squeaky Fromme was a real cultist. Moore represented the individual insanity of the time and Squeaky the social insanity,” Starr said. The assassination attempts — on Fromme in Sacramento and on Moore in San Francisco — also contributed to “an atmosphere of lawlessness” in Northern California, Starr said, compounded by events in the 1970s such as the kidnapping of Patty Hearst, the assassination of San Francisco Mayor George Moscone and the mass suicide of the Jonestown cult.

Others say the acts symbolize the breakdown of American society in the aftermath of Watergate and the Vietnam War.

“A lot of people just let themselves go, finding some reason to believe there was a political or conspiratorial explanation for their inner turmoil and concluding that if they could just act on their impulse, they could save the world,” said Todd Gitlin, a professor of journalism and sociology at Columbia University and a former leader of Students for a Democratic Society, whose books include “The 1960s: Years of Hope, Days of Anger.”