It was early morning when Ben Smith drove his SUV to the top of Mountain High Ski Resort and looked south. Miles away and across a valley, he could see the menacing red glow of the bridge fire amid the dark green pines of the Angeles National Forest.

By Smith’s estimate, the fire would not reach the station for at least a day.

That’s when the fire exploded.

At 6:30 that evening, the station general manager was heading east on Highway 2, past the town of Wrightwood, as flames closed in on both sides of the road.

Smith had done everything he could to save the station. He was the last to flee after his team activated a battery of snow cannons to spray the ski area.

Now there was only one thought running through his mind: “I hope I make it out of here,” Smith recalled as he leaned against a wooden pole recently at the resort’s Big Pines Lodge.

It is a testament to the work of Smith’s crew and firefighters that the lodge and most of the neighboring resort escaped the hellish firestorm.

“When I left here…I expected to return to everything that was gone,” he said.

Now, about a month later, tree-cutting crews and electric trucks are crisscrossing the property. Mountain High operators are optimistic the resort will open by Thanksgiving.

“In the winter, when the snow comes, you won’t even know there was a fire here,” said Damaris Cand, customer service manager.

The Mount Baldy ski lifts are shrouded in smoke following the Mount Baldy Bridge fire on September 12.

(Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

The bridge fire broke out early Sunday, September 8, 11 miles south of the station. On Monday, the fire was on Smith’s radar as it slowly approached.

By Tuesday, the fire would “explode” – engulfing tens of thousands of acres in a matter of hours, increasing its size tenfold.

At the station staff meeting this Tuesday morning, the atmosphere was calm. The sky was still clear and painted the pinks and oranges of sunrise.

But Smith, who is vice president and treasurer of the Wrightwood Fire Safety Councill, saw potential for calamity, as winds were expected to intensify.

He asked the team to begin placing snow cannons strategically along the perimeter of the station. About 50 employees from a wide range of departments moved around the station as the sky grew darker and darker from the smoke.

Trees around Mountain High Ski Resort were burned by the bridge fire.

(Michael Blackshire/Los Angeles Times)

By early afternoon, Smith could no longer see more than 100 feet in front of him. There was no longer any way to directly monitor the fire.

Ash and debris, still burning, began to fall from the sky. At one point, a flaming stick about a foot long hit the ground.

Employees began leaving, concerned about safety and air quality.

“I got out of here around 2 p.m. and the sky was black,” said John McColly, the resort’s vice president of sales and marketing. “A lot of smoke was coming up and it had this reddish tint. …Just for the sake of my lungs, I probably need to get out of here,” he remembers thinking.

Then, around 4:30 p.m., the nightmare scenario unimaginable a few hours earlier became reality. A wall of flame more than 300 feet high, by Smith’s estimate, topped the ridge, roaring with the sound of a jet engine and blasting the station with superheated wind and debris.

What began as cautious fire protection preparations suddenly turned into a fight for survival.

Workers at Mountain High Ski Resort used snow guns to fight flames from the bridge fire.

(Michael Blackshire/Los Angeles Times)

Smith ordered staff to evacuate nearby campers. The team began creating timesheets to ensure every employee was accounted for.

Smith sent another team member running to the snow control center to activate the giant water system.

The team had stationed about 100 of its approximately 500 snow guns to defend the resort. While they could start about three-quarters of them with the push of a button, the rest had to be lit by hand.

While the majority of the staff was evacuated, Smith and a handful of employees stayed and ran around the property activating the snow cannons.

McColly monitored the progress of the fire via the station’s live camera feed — which aims to give skiers an overview of snow and weather conditions. He and countless others who had connected via social media viewed the flames in awe as they outlined the silhouette of a seemingly doomed ski lift terminal.

Smith had alerted fire crews, whom he knows personally from his role on the fire safety council and past wildfires, but they wouldn’t arrive for hours.

A Mountain High ski team recently worked on a chairlift.

(Michael Blackshire/Los Angeles Times)

In several places, massive explosions shook the ground, accentuating the roar of the fire.

The higher elevations of the station lost power first. Around 5:30 p.m., the base area also became dark. Without electricity, the water pumps of the snow guns were silent. Now the guns were powered solely by gravity, which sent water down the 500,000-gallon tanks and out through the guns’ nozzles.

As the fire ravaged the telephone poles, telephone service failed.

The number of employees remaining at the station fell to three. Then, two. Next, one: Smith.

At that time, around 6:30 p.m., fires engulfed both sides of the station. Realizing there was nothing more he could do, Smith fled.

“I wasn’t trying to be a hero,” he said. “I have a wife and a family.”

It was only during the night that firefighters were able to get to the scene.

Trees burned by the bridge fire dot the Wrightwood landscape.

(Michael Blackshire/Los Angeles Times)

Smith returned to Mountain High the next morning to assess the damage and assist firefighters. The fire continued to rage – still with hundred-foot flames, but not fanned by strong winds.

“I went through Wrightwood, and before you get to our East Resort, … you’re like, ‘Hey, it’s all gone,’” Smith said. “But then you get to the East Resort and start seeing green trees, buildings and you’re like, ‘Well, damn, it’s not that bad.'”

Not only was most of the station standing, but the snow cannons were still dumping water on the outskirts of the station.

In total, the resort had one non-essential ski lift damaged, while a few patrol and maintenance huts burned.

“I’m very proud of my team,” Smith said. “A lot of what still exists here is thanks to them. »

When the station is not falling victim to the Angeles National Forest fires, it often serves as an invaluable operations center for firefighters. Its buildings serve as a command center, its parking lot becomes a heliport and its water tanks are essential refueling stations.

“Over the years, through the fires, through the fire safety council, just to have partnerships with all of these groups and to be able to have all of these contacts at your fingertips is incredible,” Smith said.

It took nearly a month to secure the station and restore power, allowing the entire team of employees to return safely.

In early October, crews worked to repave Highway 2, which was cracked and scarred from the fire and efforts to fight it.

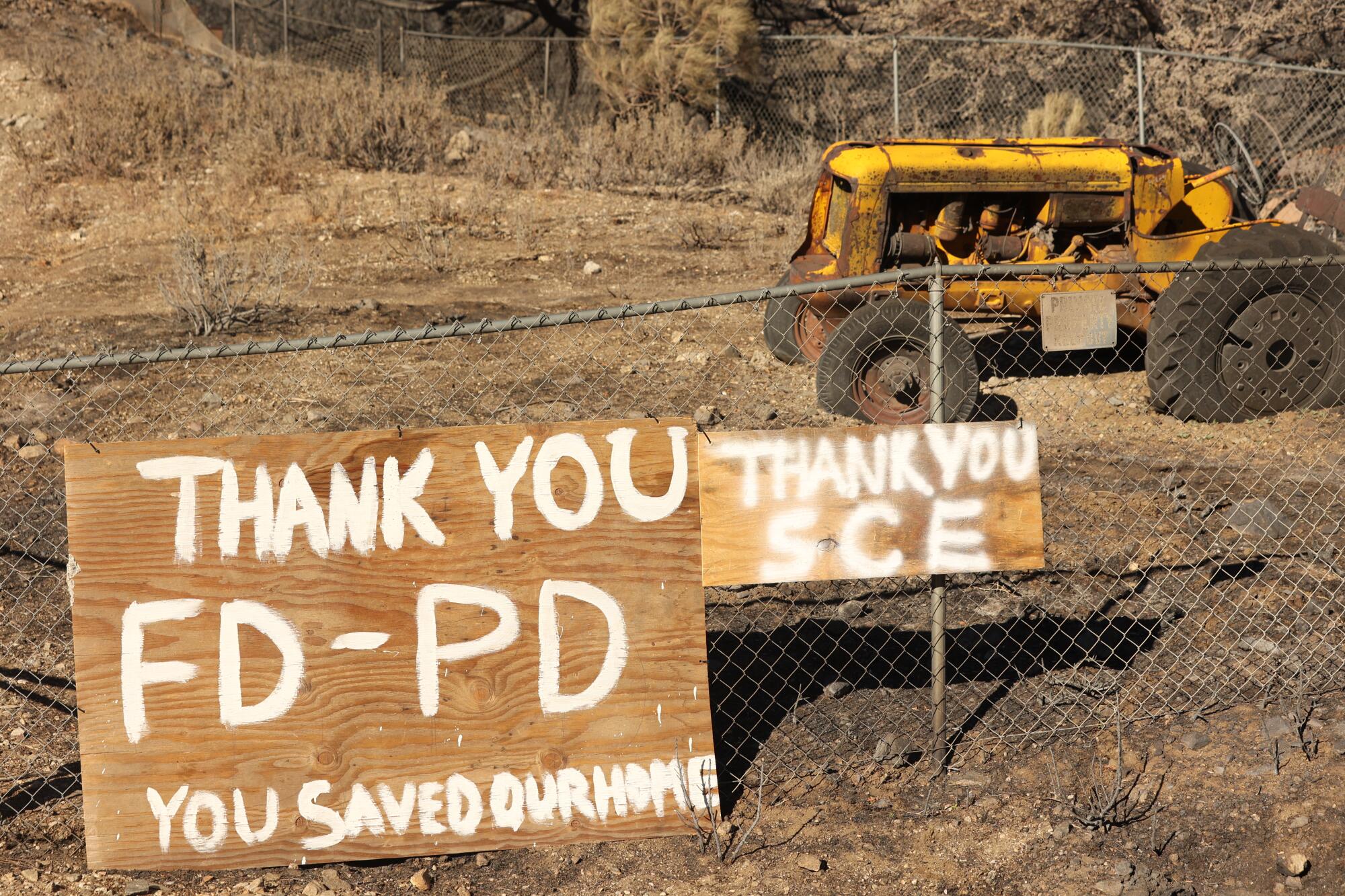

A sign in Wrightwood thanks emergency crews following the bridge fire.

(Michael Blackshire/Los Angeles Times)

In Wrightwood, residents adorned the town with homemade signs.

A piece of plywood, attached to the Wrightwood town line sign, with black spray-painted letters read “Thanks for Saving Us.” A colorful hand painted sign with a cartoon fire truck hanging next to the fire station. “We [heart sign] you,” it reads.

McColly had returned to his office in a historic cabin, which now smelled of wet rags and old cigarettes.

He turned his computer screen to display a special seasonal subscription offer for the 100th anniversary of the station. Customers would receive a special hat and pin commemorating the season. And the resort would donate $25 to the American Red Cross disaster relief organization.

The Red Cross was on scene after the fire to support relief efforts, McColly said. Partnering with the Red Cross is a way of saying thank you and passing on help.

“They were great to work with,” McColly said. “They really helped us a lot.”