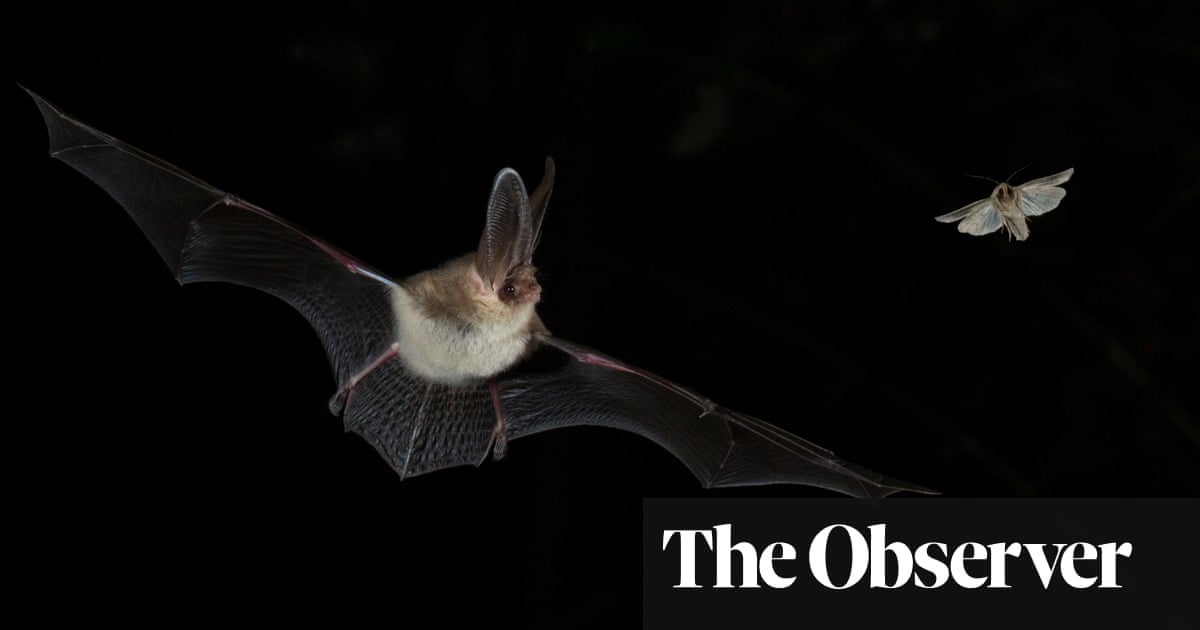

Conservation groups across England are seeing more and more malnourished bats, while wildlife experts warn that the summer of decay is reducing the insects, butterflies and moths they feed on.

Groups in Cambridgeshire, Norfolk, Worcestershire, Essex and South Lancashire said they were seeing an increase in the number of “starving” or “underweight” bats, often young ones, which had to be rescued and cared for by volunteers. In some places, they were seeing fewer bats than usual in the summer.

Insect populations have been declining in the UK for decades, driven by the climate emergency and widespread pesticide use. Some believe this has been made worse by this year’s record rainfall.

“Any decline in insects could have a serious negative impact on the UK’s 17 breeding bat species, as they all feed on insects,” said Dr Joe Nunez-Mino, spokesman for the Bat Conservation Trust, which runs the National Bat Helpline and refers serious rescue cases to local volunteers.

Last year, the charity found that UK populations of two species – the brown long-eared bat and the horseshoe bat – had declined by more than 10% in the past five years. It is conducting a long-term study to understand the impact of the climate emergency on bat species.

In the UK, bats are under threat from habitat destruction, the increasing use of artificial light and the construction of new buildings. Nunez-Mino said all of these factors affect bats and the insects they feed on.

People can help the association track bat populations through its annual National Bat Monitoring Project this summer.

Butterfly Conservation charity reports a “notable absence” of butterflies and moths this year. Conservation director Dr Dan Hoare said: “This is likely due to the wet spring and cooler than normal temperatures. Butterflies and moths need warm, dry conditions to be able to fly and mate. If the weather doesn’t allow them to do this, they will have fewer opportunities to reproduce.”

The charity is encouraging everyone to take part in its annual Big Butterfly Count before 4 August, another leading citizen science project that is checking in on the health of UK populations. As indicator species, the presence – or absence – of butterflies and moths shows the health of the environment and wider ecosystem.

In eastern England, experts were called in to rescue malnourished bats in Cambridgeshire, Bedfordshire, Northamptonshire, Lincolnshire, Essex and Suffolk this summer.

“Some of our keepers are looking after 20 bats,” said Jonathan Durward, conservationist and treasurer of the Cambridgeshire Bat Group, adding that most are young and pups who are “incredibly” underweight: “They are all starving.”

He thinks many bats, especially young ones, are traveling farther and flying longer to find food. As furry mammals, bats need to warm up after getting cold and wet, expending vital energy that nursing mothers would normally use to nurse their young in June and July.

“It’s been extremely wet, cold and windy here this summer,” Durward said. “But if they don’t get out in the cold and rain, they lose a night’s worth of food.”

after newsletter promotion

According to Durward, most of the young bats they rescue weigh 50 percent of what conservationists would expect.

“They are much thinner and lighter than in previous years. Almost all of them are in poor health, not just underweight,” he added. He added that the less bats eat, the less healthy they are and the more vulnerable they are to parasitic infections.

At the East Winch Wildlife Hospital in Norfolk, vets treated almost twice as many bats as usual. “We had a high number of young compared to last year. You might wonder if the adults are struggling to find food and therefore produce milk for the babies,” said the centre’s deputy director, Alice Puchalka.

Thirty kilometres away, in Pensthorpe Country Park, reserve manager Richard Spowage said rangers had seen significantly fewer bats this summer than usual.

“We’re seeing fewer bats in the evening, but we’re also not seeing the butterflies and moths we would expect. They’re not emerging in sufficient numbers and they have little time to breed and lay their eggs.”

According to Spowage, the decrease in breeding insects this year will likely translate into fewer insects next year. “It’s a downward spiral.”